Those of us on the East Coast are finally making our way out of this year’s polar spell with March expected to be in the cuddly upper 30s to low 40s Fahrenheit. We’ve been scurrying back and forth between buildings and doing what we can to generally avoid the cold. But all things considered, for many of us city dwellers, we have it pretty easy. We can venture out into the sub-zero temperatures if we so choose, but staying in with a few hot toddies and Netflix is much more pleasant. But what is it like to be really cold?

Freezing to Death

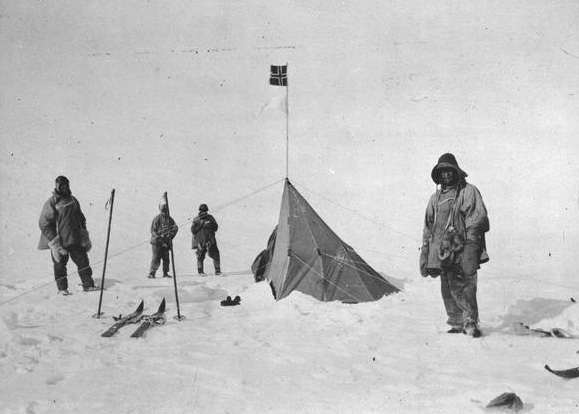

In 1912, Robert Falcon Scott led a team of five men on the final leg of the Terra Nova Expedition to reach the South Pole. They hauled their supplies on sledges over crevasses and through blizzards with highs of -30 °F (-34 °C) during the day and lows of -47 °F (-44 °C). After nearly five months, Falcon and his men reached the South Pole on January 17th. In his journal, he wrote:

"The Pole. Yes, but under very different circumstances from those expected ... Great God! This is an awful place and terrible enough for us to have laboured to it without the reward of priority. Well, it is something to have got here."

However, the next day he discovered the tent and notes belonging to Roald Amundsen, a Norwegian explorer, whose team had beaten Scott to the Pole by a month. At the bottom of the world, Scott and his team turned back to begin their 800-mile return journey on foot. They would never make it.

Captain Scott and his team by the Norwegian tent left by Amundsen at Polheim (Norwegian for "Home of the Pole"). Photo: Wikipedia

Despite poor weather, Scott and his team made solid progress. They traveled 300 miles by February 17th before Petty Officer Edgar Evans succumbed to his injuries, including a blow to the head after falling into a crevasse at the base of the Beardmore Glacier. The remaining men pulled their sledges across the Ross Ice Shelf in some of the worst conditions ever recorded for that area. Captain Lawrence Oates, who had suffered a shattered thigh from a bullet during the Boer War and whose pain was intensified by the cold, was slowing the team’s already slow progress. He had severely frostbitten feet leaving Scott to note, "Oates' feet are in a wretched condition... The poor soldier is very nearly done."

Oates suggested he be left behind in a sleeping bag in order to speed up the remaining men’s return journey. His companions ignored this request. On March 16th, he woke up, walked out of his tent barefoot into a -40 °F blizzard and reportedly told the men, "I am just going outside and may be some time."

His severely frostbitten feet must have already been nearly black in color. At first, the water outside of his muscles, blood vessels, and nerves would have crystallized. The sharp ice crystals can puncture cell membranes, causing a disruption of the normal cellular salt balance. This osmotic disruption causes initial tissue damage. Ice crystals then form inside cells, mechanically destroying cells from within. As Oates’ feet were freezing, his body may have pumped periodic waves of blood flow to warm them. This would have temporarily thawed his feet before they froze again. But this thawing and refreezing cycle in fact likely did more damage to the cellular integrity of his feet. If he had lived, his feet would have required amputation.

Ice mask, C.T. Madigan, between 1911-1914. Photograph by Frank Hurley Source: State Library of New South Wales

In near-freezing water, an average human’s body temperature will drop to 95 °F (35 °C) in a matter of minutes. Oates, who was clothed aside from his feet, stepped out into subzero air, which immediately began lowering his body temperature more slowly. Given his already weakened condition, he would have had a much more difficult time than most healthy men his age (32) to keep his core temperature at 98.6 °F (37 °C).

As his core temperature dropped to 95 °F, the upper threshold for mild hypothermia, his teeth would have begun to chatter and his body would have shivered uncontrollably. By shivering, the body attempts to burn energy to prevent core temperature from dropping any lower. His covered skin would turn white as his capillaries were restricted, saving the warm blood for his body’s core. Today, people suffering from mild hypothermia are wrapped in Bair Huggers, blankets that pass warm air over the body, to recover.

Oates likely trudged further away from his tent, ensuring that the team wouldn’t find him; his body temperature dropping with every step. At 87.8 °F (31 °C), he would have reached the upper limit of moderate hypothermia. At this point, he would have stopped shivering as his body abandoned its efforts to warm itself. His breathing would have slowed and the carbon dioxide in his blood would have begun to accumulate, making his blood more acidic. His heart would be pumping slower, his blood — more acidic and thicker — would course through his body more slowly. He may have felt the need to urinate because the retention of fluids in his body’s core stimulated his kidneys to get rid of extra fluid volume.

If he could see anything through the blizzard, he would have had trouble making sense of what he saw. Moderately hypothermic, he would be confused and amnesiac. He would have trouble recognizing the faces of his companions if they had followed him.

His wandering likely resembled stumbling due to his frostbitten feet, but now he would have lost most of his fine motor reflexes and would have undoubtedly fallen. Lying in one of the harshest colds on the earth, he may have looked up to see Scott’s hut only 50 feet away. He could have realized that they had severely miscalculated how far they actually were and had in fact made it to safety. Any attempts to yell for help would have been difficult, as his speech would have been too slurred. Dragging his stiff limbs through the snow, he wouldn’t have made it far before he realized he had been hallucinating. They were still hundreds of miles away.

Modern photograph of the interior of Scott's hut, unchanged since 1913. Cape Evans, Ross Island, Antarctica. Photo: Flickr

Lying in the snow, he may have felt the sudden sense of being on fire and attempted to undress. People who suffer moderate to severe hypothermia are sometimes found naked in what is called “paradoxical undressing.” This phenomenon is attributed to two possible reasons: one is that the brain’s temperature regulator malfunctions, and the other is that muscles keeping blood restricted to the body’s core become exhausted and release a surge of warm blood to the cold extremities, causing the sensation of burning.

At 82.4 °F (28 °C), Oates would have fallen unconscious, and his heart, already beating more slowly, would have begun to beat irregularly. He no longer would have any automatic reflexes. His temperature would drop further. Down until 77 °F (25 °C), the most basic portions of his brain would have been auto-regulating his brain temperature, to keep it warmer than the remainder of his body. This now failed. Dropping to 68 °F (20 °C), his breathing would stop, followed by his heart.

He would now have entered profound hypothermia. He would have no vital signs. Alone in a blizzard, he froze. His body was never found. He died, but at the start of profound hypothermia, he was not technically dead.

The Ross Ice Shelf at the Bay of Whales - the point where Amundsen staged his successful assault on the South Pole. Photo: NOAA

You’re not Dead Until You’re Warm and Dead

In 1999, Anna Bågenholm, then a 29-year-old doctor in Sweden, was skiing with friends when she lost control and fell head first through a layer of ice covering a stream. Her upper body stuck under 8 inches of ice, she found a pocket of air. Her friends could not pull her out. They struggled for 40 minutes before she lost consciousness. Eighty minutes after Anna fell in the stream, rescuers finally freed her. Her heart had stopped and her core temperature was 56.7 °F (13.7 °C), the lowest ever recorded for an adult.

Anna was transported to the Tromsø University Hospital emergency room. Doctors there had experience with patients suffering from hypothermia, but never this extreme. Over nine hours in surgery, the doctors brought her back to life. They immediately got her heart beating again and put her breathing under the control of a ventilator. Warming a body from such drastic lows can be done in multiple ways, but the most effective for patients with profound hypothermia is cardiopulmonary bypass.

Cardiopulmonary bypass uses a machine to take over the normal pumping of blood and gas exchange performed by one’s heart and lungs. This method has been shown to be the most effective way to treat severe hypothermia compared to other methods such as the more passive rewarming of blood known as continuous arteriovenous rewarming (CAVR, which requires the heart and lungs to be functioning) and by adding warming fluids intravenously or into body cavities.

Cardiopulmonary bypass also avoids the potential for “rewarming shock.” In 1980, 16 Danish fishermen were rescued from a shipwreck in the North Sea. Once safely aboard the rescue ship, they were taken inside and given hot drinks. They all dropped dead right then and there. It is believed that the sudden deluge of cold blood into their hearts led to cardiac arrest.

Anna was extremely lucky. According to her doctors, when she fell into the stream, her brain cooled very quickly, dramatically lowering the amount of oxygen it needed. Therefore, when she was rewarmed, she had little to no discernable brain damage. Today, she is a radiologist in Sweden with no effects of her trauma save for a few minor nerve issues in her hands and feet. Her successful recovery has also created a new technique called “therapeutic hypothermia” in which patients suffering from cardiac arrest or stroke are cooled to minimize their oxygen requirement, thereby potentially limiting the amount of brain damage.

Anna Bågenholm being resuscitated by doctors at the Tromsø University Hospital. Photo: BBC

In the US, there are about 1,300 hypothermia deaths per year. Men, perennially refusing directions and help,die from hypothermia twice as often as women do. And many of these deaths are attributed to older adults, who are more susceptible to hypothermia than are the young and invincible. But regardless of age or gender, it is painfully cold out. So stay in, make some tea, and get started with Season 3 of House of Cards if you haven’t already.